Imaging a 16th-Century Spanish One Real with Modern Tools

For my high school graduation—many moons ago—I received an unusual gift: four Spanish silver coins dating to the 1590s. They came from Fred Drew, a friend of my father and an antiquities dealer based in Lima, Peru. Fred was a collector in the old-school sense. His house smelled like dust, books, and history, and every surface seemed to hold something improbable. I loved visiting, even if his version of Indiana Jones involved fewer whips and more paperwork.

I had long forgotten about the coins until recently, when I found them tucked away in a drawer. That rediscovery sent me down two parallel paths: understanding their historical context, and examining them through the lens—yes, the pun is intentional—of my daily work in imaging and materials analysis.

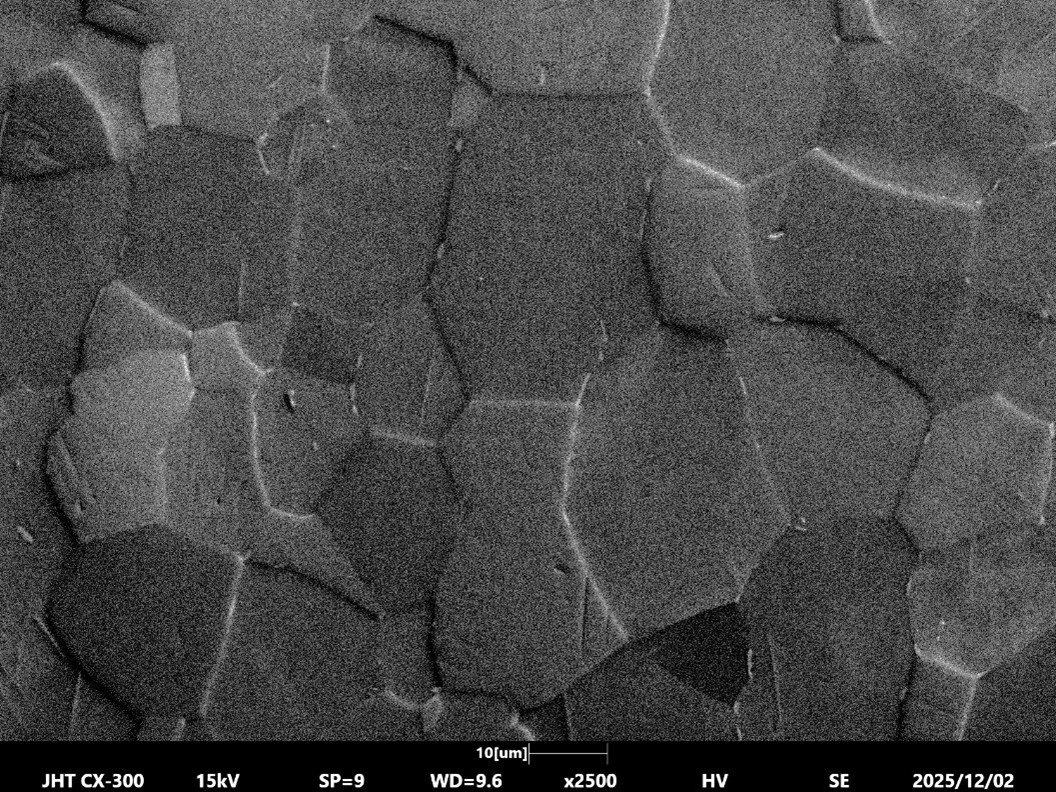

Fig 1: Spanish One Real coin made in Peru

Macuquinas: Function Over Form

The coins are known as macuquinas (Fig 1), hammered coinage minted in Spanish America during the reign of Philip II of Spain. These particular examples were struck in Peru in the late 1500s, a time when no mechanical minting presses existed in South America. Instead, coins were produced using hand-cut dies and struck with hammers and chisels.

Of the four coins I received, two are One Real pieces and two are Two Real pieces, all silver. Coins from this family ranged from small fractional denominations up to the Eight Real coins—the famous “Pieces of Eight” of pirate lore (Fig 2). The Real was a unit of weight, not geometry. A full Eight Real coin weighs roughly 26–27 grams. The One Real coins in my set weigh around 3 grams.

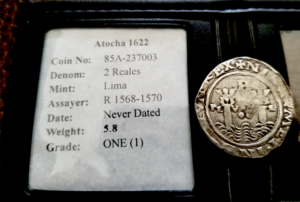

Fig 2: Spanish One Real coin found on the shipwreck of the Atocha 1622.

Because weight was what mattered, size and shape were largely irrelevant. As a result, macuquinas are famously irregular: off-round, uneven in thickness, and asymmetrical. Many surviving examples are also underweight. This wasn’t necessarily mint fraud; traders often clipped a small amount of silver as a “commission,” a practice tolerated enough that clipped coins still circulated.

- 8 Reales: ~27 grams

- 4 Reales: ~13.5 grams

- 2 Reales: ~6.75 grams

- 1 Real: ~3.375 grams

- 1/2 Real: ~1.69 grams

Most macuquinas were removed from circulation by the 1700s and re-minted using modern presses, making surviving examples comparatively scarce.

Imaging a Coin Without “Improving” It

The insignias on my coins—mint marks and assayer initials—are heavily worn and partially obscured by corrosion. I deliberately chose not to clean them. From an analytical standpoint, corrosion is information, not contamination.

Using one of our stereo microscopes, I imaged the shiniest One Real coin (Fig 3). Image stitching allowed us to generate a full-coin view with depth and texture intact. This provides something close to a “human eye” perspective, revealing the faint crest, lettering remnants, and the uneven strike typical of hammered coinage.

Fig 3: Spanish Real One imaged using Leica M205 stereo microscope and Enersight image stitching software

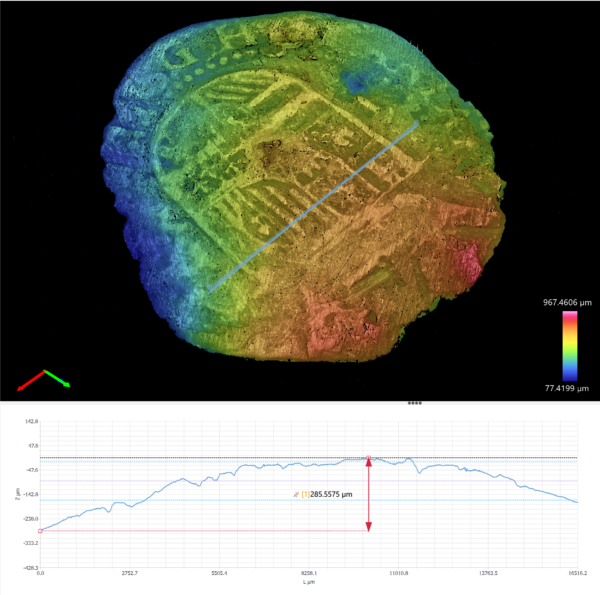

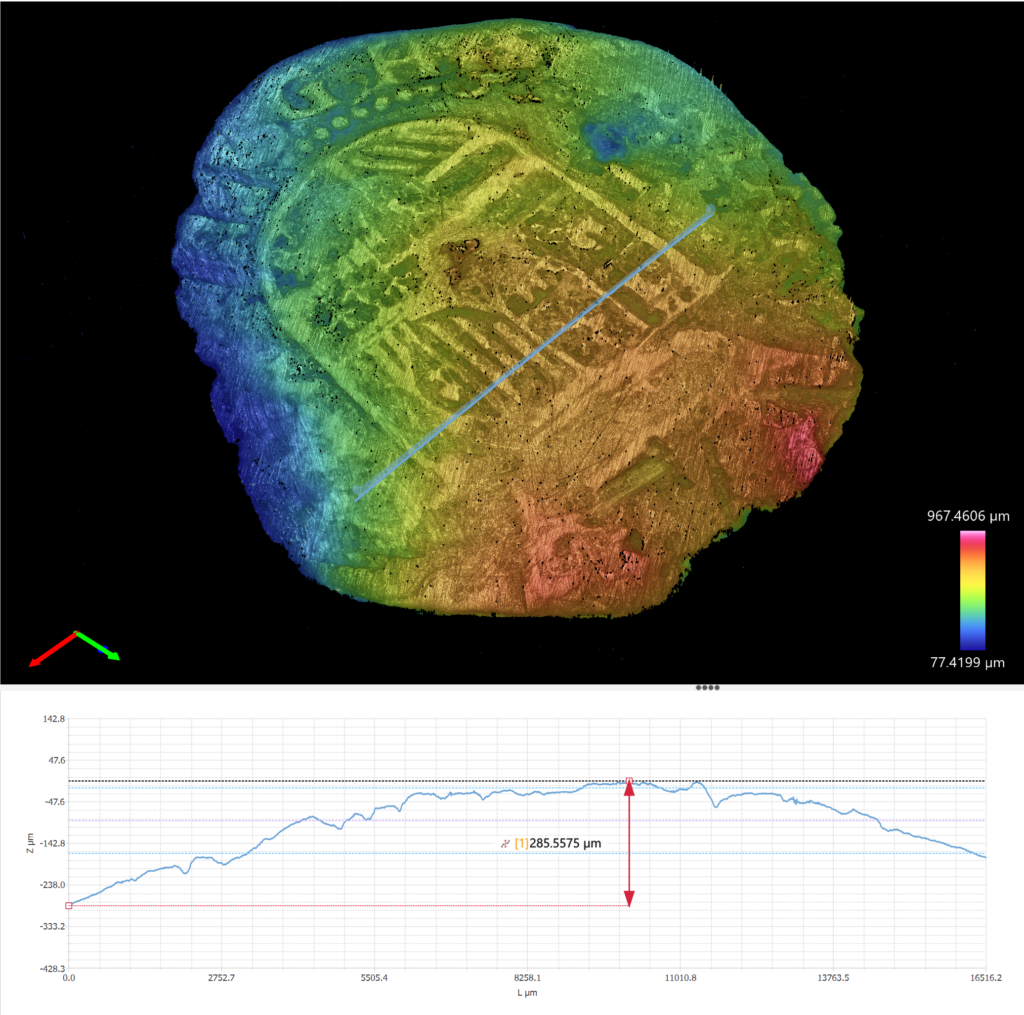

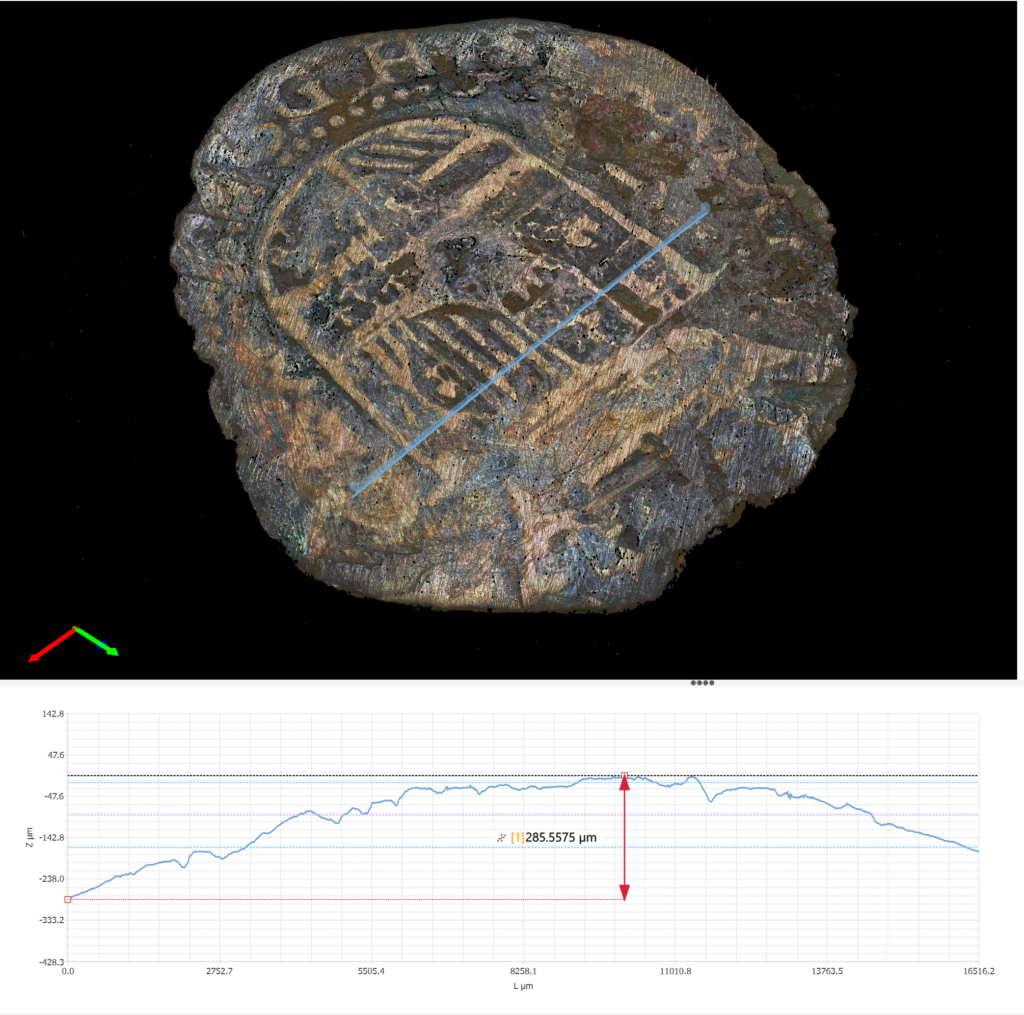

Surface Topography: Wear Tells a Story

We then performed surface profiling using a profilometer. Unsurprisingly, the coin shows relatively low surface relief (Fig 4). Four centuries of handling and circulation have flattened most of the original struck features. The profile shows a generally flat central region with a gentle overall curvature—likely a combination of original hammering and long-term mechanical wear.

This is an important reminder: what we see today is not just the result of minting technology, but of decades (or centuries) of economic use.

Fig 4: Surface profile of One Real (Image generated using Sensofar S Neox)

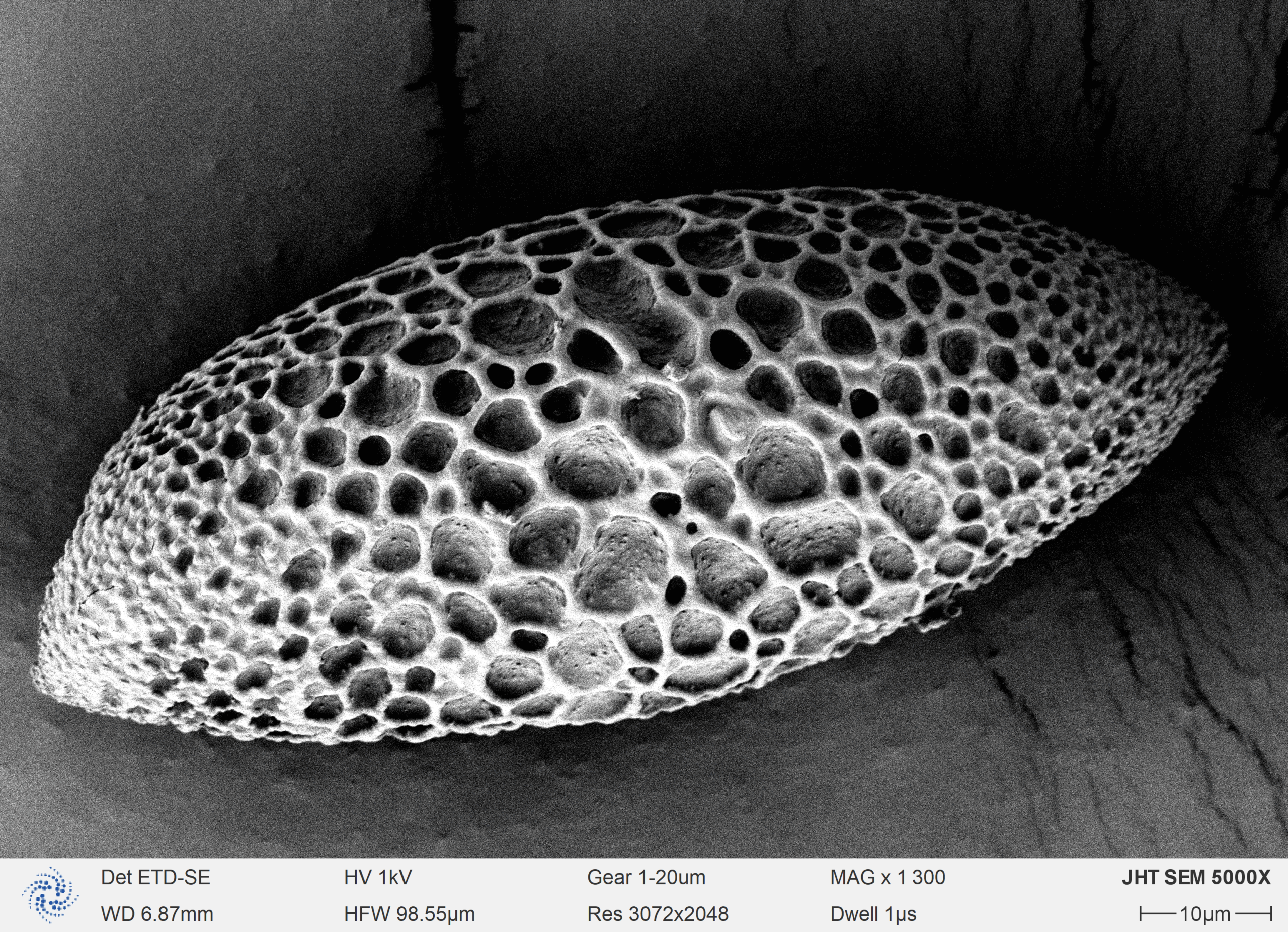

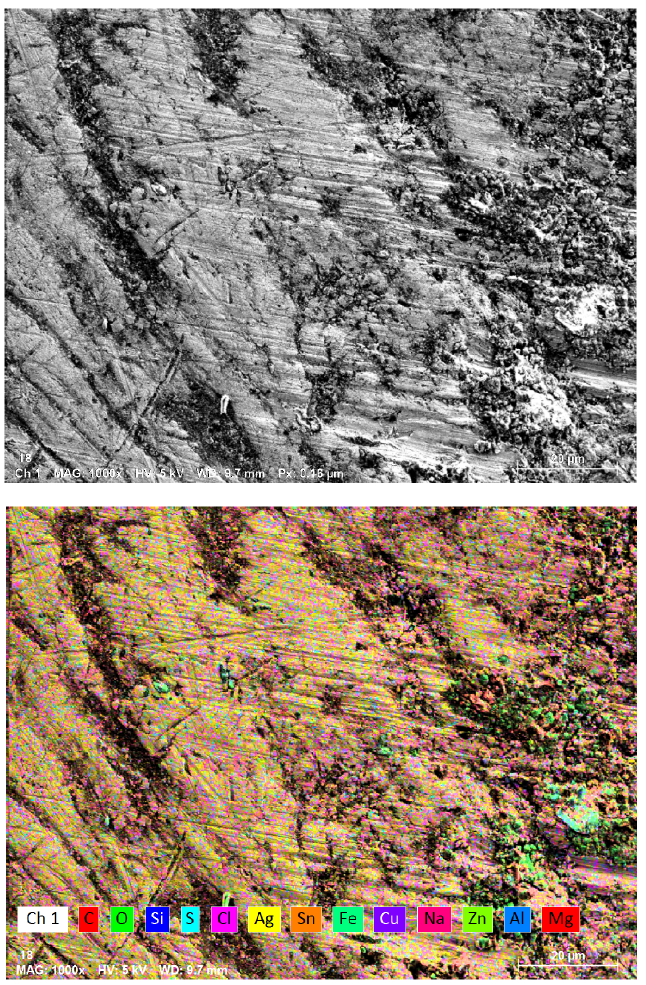

SEM and EDS: Composition Beneath the Surface

To dig deeper, we imaged selected regions using a FE SEM and performed EDS analysis. Historically, these coins are described as silver, but “silver” in the 16th century rarely meant pure Ag (Fig 5).

Fig 5: SEM image and EDS scan (Image taken with CIQTEK Field Emission SEM 5000X, EDS scan done using Bruker X-Flash 7100)

The EDS results confirmed that silver is the dominant element, but at a lower percentage than I initially expected. This aligns with historical records: macuquinas often contained alloying elements and impurities, either intentionally added or introduced through ore variability and refining limitations.

We also detected elements associated with corrosion and environmental exposure. Because the coin was not cleaned, the surface chemistry reflects centuries of storage, handling, and oxidation. From a materials perspective, this layered surface—metal, alloy phases, corrosion products—is far more interesting than a polished artifact.

Old Money, Modern Perspective

These coins were once a globally accepted currency, used across the Spanish Americas and beyond. Today, they’re a reminder that manufacturing tolerances, material purity, and surface finish are deeply tied to available technology—and to economic priorities.

Four hundred and thirty years later, it’s striking (pun unavoidable this time) how much information still lives on the surface of a small, battered piece of silver. With modern imaging tools, even a worn macuquina still has plenty left to say.